«Music is my first partner»

Zurück

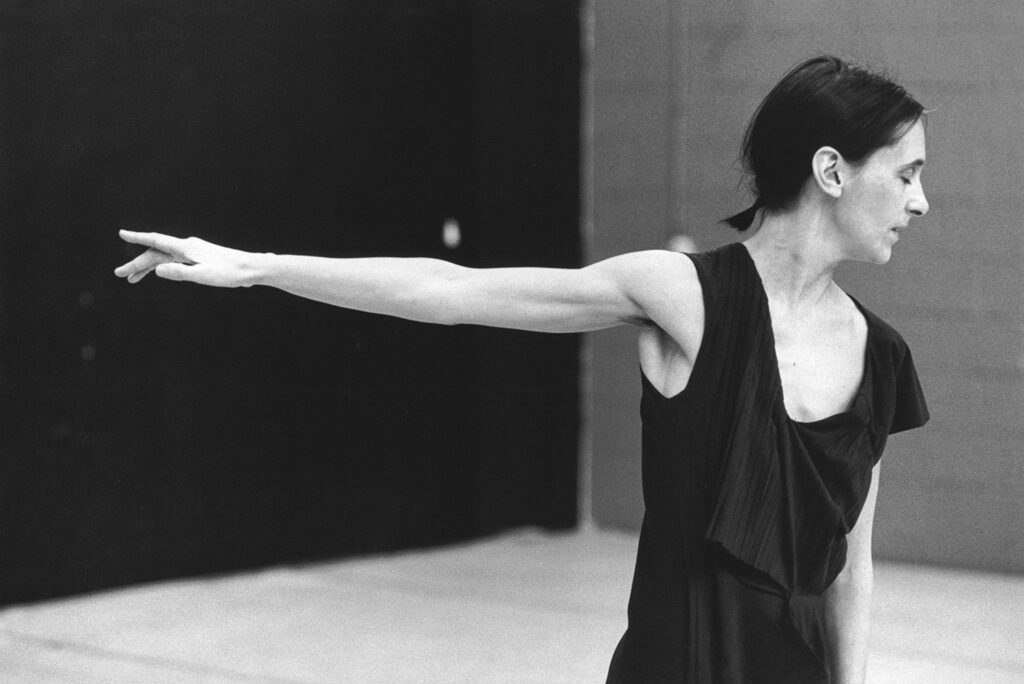

Lydia Rilling: In September 2017 you opened the red bridge project by dancing Violin Phase at Mudam. This piece dates from 1982 and was your very first choreography. How does it feel to dance this work again?

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker: It is exceptional to stay with a dance for more than 35 years. This dance is the DNA of my practice as a performer and also as a choreographer. It is sheer pleasure. Somebody described the dance once as a squared circle. Maybe that is a good definition of my way of dancing. There is a whole number of aspects that are very characteristic of the dance: the underlying geometry, the notion of maximizing a minimal amount of vocabulary, the natural movement—the movement follows the architecture of the body because there is a very big notion of flow but no architectural extension of the body. For example, the arms never go over the shoulders. It is almost close to folkloric dances—turning, stepping and hopping as the most simple ways of dancing.

I am grateful that I still can dance this piece and that my body allows it. Of course, my body carries the memories of a lifetime experience. On a professional and on a private level: being a choreographer, a dancer, a mother, a woman. That is all in it.

LR: What role does the space around you play in Violin Phase?

ATDK: It is different in a black box theatre than in an open space like Mudam or MoMA. In the black box you have the frontal space and the sides. But at Mudam or MoMA the public is standing around you and shapes the space. It is sort of a natural way, as in a market place, where somebody starts to turn and to dance and everybody forms a circle around him or her. As the dancer, you sculpture the space around you through your steps, gaze and upper body and the flow.

A circle, as it forms the dance floor in Violin Phase, has a number of characteristics. It is very continuous, allows endless variations, and can eventually become spiraled. It is like a branch of infinity. But a circle can also be closed and not leave an opening. More and more with age, for me the circle has become less and less an underlying pattern but rather a volume. With a circle, you basically have four elements: a center, the border, the space inside and outside. You have a territory that is defined. The circle is the most democratic form also in relationship to the performer and how it is perceived because everybody is at the same distance from the center. It is a very harmonious form.

LR: You always have been a contemporary listener—starting with Violin Phase that was only 15 years old when you developed your choreography, to Gérard Grisey’s chamber music composition Vortex Temporum from 1994–1996, on which your milestone work Work/Travail/Arbeid is based. There is no other choreographer of your standing with such an intimate relationship to contemporary music. What has always drawn you to contemporary music—as a listener, dancer and choreographer?

ATDK: That is an interesting question. Initially it had to do with my environment at Rosas. I have always been surrounded by very good musicians, composers and conductors. The physical presence of the Ictus ensemble right next to Rosas and the direct interactions—you cross the musicians and hear their music in the rehearsal space—have been a source that shaped my knowledge of music and incited my interest in contemporary music. In addition, my collaboration with Bernard Foccroulle has been very important to me as he guided and invited me to discover a lot of music. Thierry De Mey was important too because he comes out of film but his interest was never limited to contemporary or classical music. He had a very wide interest in music: Ancient music, popular, jazz, ethnic music—music «tout court». Music has been my first partner through these people.

Music always reflects the world and the time in which it was made. Something quite crucial happened from the beginning of the 20th century onwards. The natural bound between music and dance was to a certain extent not broken but at least questioned. Even though some of the great works of the 20th century were written with a connection to dance: Le Sacre du printemps, Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, Jeux… These works mark the history of contemporary music. Nevertheless, because of the explosion of harmony and the absence of pulse this natural bond between music and dance was seriously questioned or even abolished. However, I do not find it a moral responsibility but I have always had a very keen interest in the music written after 1900. I have a strong relationship to Steve Reich but also to Béla Bartók. Scores like Gérard Grisey’s Vortex Temporum and Violin Phase by Steve Reich are at the same time an invitation to dance and a challenge. 30 years ago for me the music of Violin Phase was like a fiddler standing up on the market and saying: «I am playing the violin and you are going to dance.» Vortex Temporum is an extremely complex work. It was only after many years of learning how to choreograph by taking on challenging scores that went from Monterverdi to ars subtilior—the 13th century music that is very layered and polyphonic—and by going step by step through how we can embody those ideas, how I can find a choreographic answer to this musical statement, that a couple of years ago I felt like I had enough craftsmanship, understanding, knowledge from that music to develop a choreography. So it is an ongoing search.

LR: If contemporary music often does not offer a «natural» bond with dance what does a composition like Grisey’s Vortex Temporum offer you instead?

ATDK: The specific status of this music. This music is hard to categorize because it has so many different aspects—from the musical material to the pulse that becomes liquid. This music is very primal and structured at the same time. For me, the effect of seeing the musicians play this music, and their physicality, have been crucial—the proximity of the instruments and the physical action. Moreover, Grisey has developed a nearly scientific approach to what sound is. He analyzed sound as a material with a computer and then put the results back into acoustic music. This is a very interesting procedure. To a certain extent, working with ancient music, such as ars subtilior with its complexity, trying to find choreographic solutions to embody this complexity, helped me to find my way to approach the complexity of music like by Grisey. It is closely connected to my fascination—like many composers—with counterpoint: in perceptibility, complexity, in clarity and in flow.

LR: You mentioned the important role of the physicality of the musicians for the development of your own work. Is this physicality the main reason why you always prefer to perform with live musicians?

ATDK: I like this natural bond between music and dance. It is the most natural way when somebody takes the violin and starts to play or to clap [starts clapping herself]. The most simple way to make music is singing. It happens through the body. Even playing an instrument, which is the body’s prolongation, creates something through the body. It was the effect of the physical proximity of Ictus. My practice and my craftsmanship have been highly influenced not only by analyzing scores of composers but also by observing the practice of musicians—how they organize their time and their space, how they work, make music together. I stole a lot from them [laughs].

LR: Your work is performed all over the world. However, Luxembourg has presented your work from an early point on. Tell me about your relationship to Luxembourg.

ATDK: I have a very long relationship to Luxembourg. 2004 was the beginning of the close relationship of Rosas, myself and the Grand Théâtre during which nearly every year we have come to perform here. You must know that for a dance company like Rosas faithful partners are absolutely crucial to create structures and the possibility to develop our work continuously. There are not that many places where we have a relationship to organizers, people who help us to produce, and with audiences over many years: Luxembourg, Brussels, Antwerp, London. Luxembourg and the Grand Théâtre—first with Frank Feitler, now with Tom Leick—was one of these places where I really had a very strong sense that we are building something with an audience. Over all those years, the theatre has been an extremely loyal partner. This has been of vital importance to the continuity of the work.

LR: What does it mean for you as an artist to discover other cultural institutions and new audiences in Luxembourg? What does the red bridge offer you?

ATDK: This is the first time that I see a collaboration between different houses in Luxembourg. It is quite rare that organizers in cities are not fighting their territories but work together. To perform at Mudam, Grand Théâtre and the Philharmonie gives me, as well as the public, the opportunity to fuse things that belong together but often are difficult to bring together. It corresponds to different areas that interest me. People can see the evolution of the work and are confronted with different aspects of it. As said, since the 1980s music has been my first partner. Visual arts became important at a certain point, mainly through my collaboration with Ann Veronica Janssens. The aspect of working with live music, for example with large orchestra, is of course exceptional. So I think at the same time it is the continuity of the work, of something that has been built over long periods of time, and it is definitely a new phase. People speak a lot of bringing different disciplines together, visual arts, music, dance, theatre but my experience of many years is that very often communities are quite gated. Visual art people go to visual art, classical music people go to classical music, ballet people go to ballet performances etc. So I am really very happy that we were able to build this program that extends over a full year and that started at the very beginning with Violin Phase and will close with Mitten wir im Leben sind/Bach6Cellosuiten.

LR: If you look at your five works red bridge project presents—ranging from 1982 to 2017—do you mainly see the differences between them or the continuity they outline?

ATDK: They span a long period of time and there are big gaps between them. But they all have a very strong relationship to music. That is important. They go the very early piece, Fase, where I dance myself, to Achterland, which was the first form where I brought music and dance together and choreographed the musicians into it. It is also the first time I choreographed for male dancers. Verklärte Nacht was a new way of dealing with repertoire: I rewrote my choreography. It was something quite crucial for me in my relationship to the musician and conductor Alain Franco (who also conducts in Luxembourg). Coming to Bach and the Cello Suites: it has been an exceptional experience to work with Jean-Guihen Queyras. It is nice that I start with Violin Phase and finish with Bach where I dance myself. Because before I am choreographer I am still a dancer first.

–

Lydia Rilling is a musicologist, curator and music journalist specializing in contemporary music and music theater. Since 2016 she has been Chief Dramaturg at Philharmonie Luxembourg where she also directs the rainy days festival. She studied Musicology and Comparative Literature in Berlin, Paris, and St. Louis, was a Visiting Scholar at Columbia University in New York and taught musicology at Universität Potsdam from 2011 to 2016.