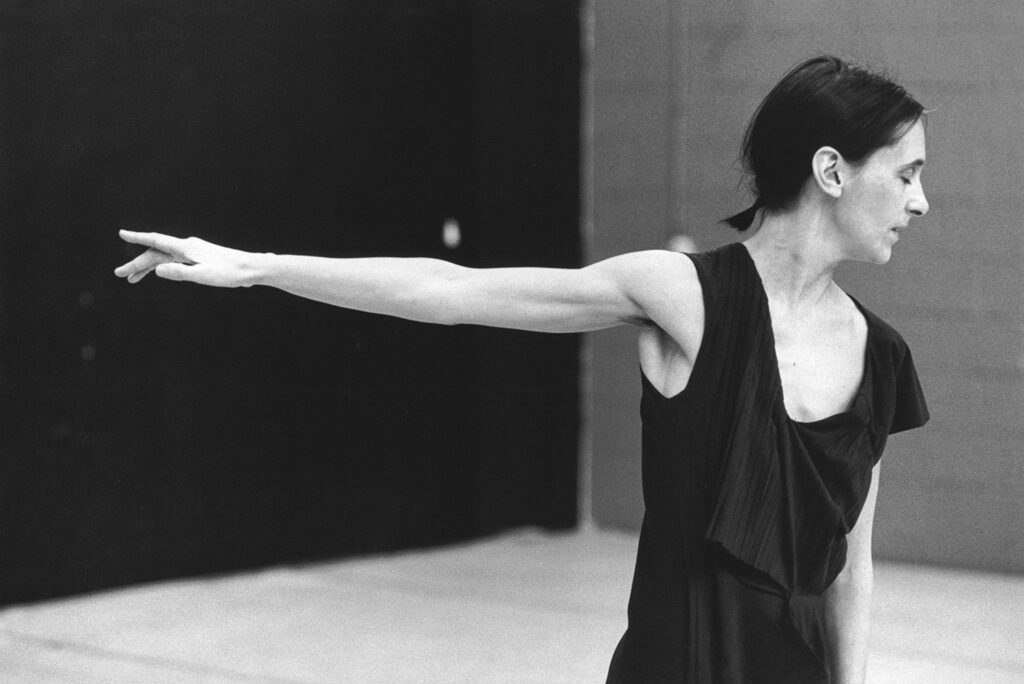

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker: A Portrait

Back

«What is needed is a genuinely new Western high art dance with movements natural to the personality of someone living here and now, organized in a clear rhythmic structure, and satisfying the basic desire for regular rhythmic movement that has been and will continue to be the underlying basic impetus for all dance.» These words — with which Steve Reich ended his «Notes on Music and Dance» in 1973 — could now be read as a disguised historical message. As if they were to summon a choreographer who, in the period of a modernist divorce of dance from music across the Atlantic, and of Tanztheater in Europe, would renew and reinvent a complex and diverse, structural, and above all intimate rapport between dance and music.

Eight years later Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker goes to New York to study dance at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, with Reich’s Violin Phase in her suitcase. The twenty-one-yearold leaves Mudra, Maurice Béjart’s school in Brussels, in order to pursue no loftier mission than what she laconically describes later as follows: «I was determined to learn how to choreograph, which nobody taught me how to do and this was the music I liked to dance to.» Thus was born Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich, De Keersmaeker’s first statement on choreography, which revealed an intensive correspondence between rigor in construction and affective vigor in dance expression. In these four dances, as early as 1982, De Keersmaeker’s poetic principles and aesthetic affinities emerge: a comprehensive structural approach to composing movement and sculpting space, time and energy in relation to music, an intricate play of repetition and difference that challenges and sharpens the perception of the becoming-same in the different, and the becoming-different in the same, and, above all, an economy of movement material from which various structural and expressive qualities unfold.

In Rosas danst Rosas, not only are the choreographic principles furthered; they develop into a distinctive idiom of the company that De Keersmaeker founds in 1983. «Rosas dances Rosas», or rather itself, is the title that explains the idiom—a subtle fusion between quotidian gestures and abstract formal movement, as well as the punky attitude of four young angry women that work out feminine seduction into a frenzy of stamina and dépense. Rosas danst Rosas becomes emblematic for a new choreographic signature, and is furthermore widely acclaimed as part of the Flemish Wave of theater and dance in the 1980s, next to the work of Jan Fabre, Wim Vandenkeybus and Jan Decorte.

Following in quick succession from 1983 to 86, the next two performances of the Rosas company—Elena’s Aria and Bartók/Aantekeningen—point in another direction: the theatrical strain that will later evolve to include various experimentations with spoken and sung word, with actors and musicians. To account for the dramaturgical reason behind resorting to heterogeneous sources (literary texts, films, folk songs) De Keersmaeker borrows the words of Yvonne Rainer: «When I talk about connections and meaning, I am talking about the emotional load of a particular event, and not about what it signifies. Its signification is always very clear, I don’t deal with symbols, I deal with categories of things that have varying degrees of emotional load.» This is to say that words, images and dances alike in her performances never conform to a narrative, or a symbolic plot, as, for instance, in Pina Bausch, yet are always meaningful, expressive in material juxtapositions. Hence, to give an example, in Elena’s Aria, stillness, the movements of loitering on chairs, fidgeting around them, or spilling over from one to another and reading a text like Brecht’s «Surabaya Johnny» do not tell a story, but are expressive of a situation—a field of tension—that De Keersmaeker describes as «what you dance and how you dance when you would actually like not to move any more.»

Over the next decades, De Keersmaeker will prove the power of choreography to turn the kind of music which would seem alien or resistant to dance, to turn the song, to turn even light and other kinds of live performative actions into movement. Transposing Cage’s dictum about music for an expanded notion of dance in De Keersmaeker’s approach signifies the structuring of various situations and materials as choreography in which dynamic, spatial, textural and corporal parameters of movement are exhaustively explored. To paraphrase Cage, everything we do is, or could be expanded into, movement.

De Keersmaeker is an unusually prolific choreographer for the extent of the diversity of her oeuvre, comparable only to that of William Forsythe, with whom she also shares intellectual accuracy and excellence in choreographic craftsmanship. Her output counts more than fifty performances in more than three decades. They range from exuberant large-scale group pieces since Ottone, Ottone (1988), based on Monteverdi’s opera L’Incoronazione di Poppea, and ERTS (1992), in which her choreography to Beethoven’s Große Fuge was presented for the first time, to more intimate duets and solos in which she advances along a specialized, or new and unfamiliar, strand of inquiry, for example, when she explores a new movement vocabulary and performative realities in her solo Once (2002) or in Small Hands (2001), created with Cynthia Loemij. De Keersmaeker’s oeuvre could be classified with respect to various criteria, such as the medium in which predominantly formal dance pieces are distilled from performances using preexisting literary texts (e.g. Büchner, Müller, Handke, etc.) or texts written during the making-process by the dancers (e.g. in Just Before, 1997; In Real Time, 2000). Her choreography for twelve young dancers, Golden Hours (as you like it), sets Shakespeare’s queer comedy (As You Like It) into gesture and dancing movement with Brian Eno’s cult album (Another Green World). Another aspect would be the styles formed from amplifying certain expressive qualities of dance and music in individual works, like the musical post-minimalism in her early works, or postmodern baroque and classicism in Ottone, Ottone, Toccata (1993), Mozart/ Concert Arias (1992), Small Hands; or the more austere monochromatic linear abstraction that can lead to great improvisational feats in Zeitung (2008). The central criterion of differentiation with respect to choice and method of composition is always music.

Music written to be danced to rarely attracts De Keersmaeker. It is, rather, the music which is conventionally considered challenging for dance or for a broader audience that is then reinvented into choreography. Her preferences lie with composers of twentiethcentury music—Bartók, Ligeti, Schönberg and Webern—or of contemporary music, like Salvatore Sciarrino or Gérard Grisey, whose Vortex temporum was the centerpiece in an eponymous choreography (2013) and choreographed exhibition Work/Travail/Arbeid (at the Contemporary Art Center Wiels, Brussels, 2015). Among more than a dozen composers she has explored since 1982, Reich holds a special place, since his music has provided De Keersmaeker with a source of construction principles in three seminal choreographies—Fase, Drumming (1998) and Rain (2001)— based on Music for 18 Musicians. These choreographies almost never literally transpose or visualize the structure of the music, but instead set analogous choreographic principles to Reich’s processes. For instance, Drumming begins with an extensive dance phrase whose elaboration contrasts with the cellular movement material and sequences in the earlier Fase, but also diverges from Reich’s original rhythmic cell in Drumming. Neither the ensuing contrapuntal techniques with which the choreographic structure in Drumming and Rain grows and differentiates, nor the geometrical patterns like spirals and stars in which a polyphonic kaleidoscope blossoms are driven by Reich’s music. Reich and De Keersmaeker are congenial in their creative evolution from «less is more» to «more is more,» whereby De Keersmaeker’s growth and counterpoint of bodily forces parallels Reich’s expansion of harmony and timbre. Both works have been recast by the major French ballet companies: Rain by the Paris Opéra Ballet and Drumming by the Paris and the Lyon Opéra Ballet.

De Keersmaeker has also produced several works in which the music was created in the course of a dance composition—as in the famous Rosas Danst Rosas, where the music of Thierry De Mey and Peter Vermeersch develops in parallel with the choreography— or the music has been set in separation from the dance, as in Zeitung and Zeitigung, in which the pianist Alain Franco interprets the historical development of harmony in Western music through his choice of compositions from Bach to Webern. In all these modalities, choreography stays autonomous and consistent in itself, faithful to its internal complexity.

Between 2007 and 2010, De Keersmaeker’s work underwent a radical shift, triggered by a collaboration with the Belgian artist Ann Veronica Janssens, notable for her exploration of light in space, and the French choreographer known for conceptualism, Jérôme Bel, in three performances: Keeping Still Part I (2007), The Song (2009) and 3Abschied (2010). What binds these performances together as a veritable trilogy is the suspension of music’s role in regulating rhythm and duration. The Song unfolds as a silent concert of a large dance assembly, under which the Beatles’ White Album furtively runs, bursting out only in a few songs.

In Keeping Still and 3Abschied, De Keersmaeker embarks on an impossible quest imbued with difficulty and risk in the desire to stage the third movement of Mahler’s Lied von der Erde, «Der Abschied,» which speaks of the acceptance of death, together with her ethical concerns for an ecologically sustainable life for the Earth. While in Keeping Still, De Keersmaeker is the dancer who explores the formless, immaterial encounter of the body and light, in 3Abschied she inserts herself as a ghost dancer amid an orchestra playing Mahler’s music, becoming its singer in the third part, in spite of her modest, amateur singing capabilities. This is a moment of transgression, of deliberate renunciation of one’s own artistry, a kind of death-offering to Mahler’s music, but also to the Earth to which the choreographer dedicates herself politically. In sum, the trilogy Keeping Still Part 1 – The Song – 3Abschied is a project that interrogates dance categorically: a sensibility to the phenomena of movement and light; composition as self-organization of individual vs. group; and lastly, the desire, reason and courage to contest aesthetic barriers in singing. After such a radical venture into silence, stillness and impotence, De Keersmaeker returns again—with a difference—to remarkable subtleties and complexity in contrapuntal choreography in En Atendant, a choreography conceived for a performance at dusk at the Cloître des Célestins in Avignon. Cesena, co-signed by the musical director Björn Schmelzer (and his ensemble Graindelavoix), presented yet another step forward in the choreographic investigation of the musical style Ars subtilior and its historical context of the calamitous fourteenth century on a large scale of vocal-kinetic counterpoint embodied in dancers singing and singers dancing. Cesena premiered at dawn in the Palais des papes at the Festival d’Avignon.

In recent years, we have seen De Keersmaeker return to the stage as a dancer again. Not only in the world-tour revival of Fase, Rosas danst Rosas and Bartók/Mikrokosmos, but also in an intimate trio codanced with Boris Charmatz, and Amandine Beyer playing violin. In Partita 2 (2012) her «walking is her dancing»—the choreographic principle she has been developing since her encounter with fourteenth-century polyphony in the Avignon pieces—is entangled with the vigorous, eloquent and wildly expressive dance idiom of Charmatz.

Last but not least, the world of dance without De Keersmaeker would not only miss an original authorial contribution that has been growing since the 1980s until the present; it would simply be unimaginable today. In 1994 De Keersmaeker founded the contemporary dance school P.A.R.T.S. together with Bernard Foccroulle, then director of the Belgian national opera De Munt / La Monnaie. P.A.R.T.S. has become the leading force in breeding generations of new choreographers and dancers in Europe who often represent the most experimental and versatile artists in the field of dance.

Recently, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker began to transmit her repertoire, particularly Rosas danst Rosas and Rain, to the younger multi-national generations of her Rosas company. She has also rewritten some of her pieces such as Verklärte Nacht, created in 1995 and reworked in 2014, and A Love Supreme from 2005 which she redeveloped in 2017. In addition, De Keersmaeker staged the opera Così fan tutte by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at the Opéra de Paris in the season 2016/17 and premiered her newest choreography Mitten wir im Leben sind/Bach6Cellosuiten.

–

Bojana Cvejić is a performance theorist and performance director based in Brussels. She is a co-founding member of TkH editorial collective, with whom she has realized many projects and publications. She wrote and edited several publications about Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, including three books published as part of the series A Choreographer’s Score. Cvejić received her PhD in philosophy from the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy, London.

–

This text was first published as Bojana Cvejić, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, Portrait, Programme du Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris, Drumming Live, July 2017. Reprint with kind permission by Opéra national de Paris.