On Work/Travail/Arbeid

Back

- Work/Travail/Arbeid is the title of your new choreographic piece, which is an exhibition, in fact: it ‹premieres› at Wiels, neither a theatre nor place where dance is usually featured, but a contemporary art center. Conceiving of and presenting a choreographic piece that is an exhibition is far from self-evident, so that is what I would like to speak to you about here. To begin with, what are the essential differences between what you have done for theater and what you will do at Wiels?

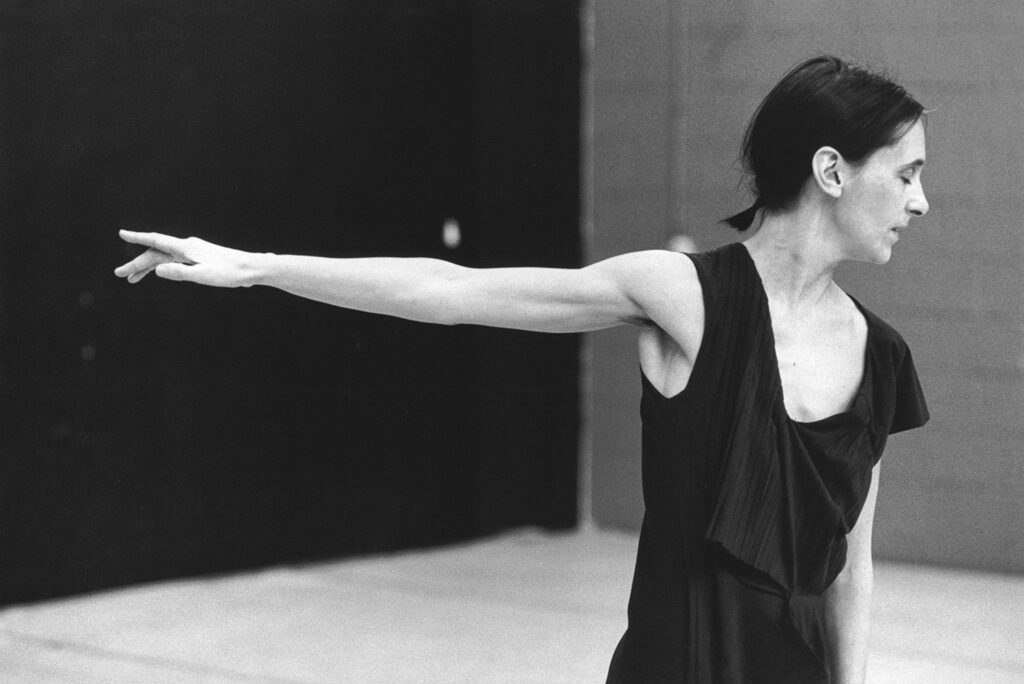

Answering your question means first delving into what choreography is, and as I see it choreography is about organizing movements in time and in space. The usual space for choreography is the frontal space of the theater, which establishes a relationship in which the audience is fixed and the movement happens onstage. And the time of a choreography’s unfolding is a framed time: a performance starts at a given time, say 8:00pm, and ends an hour or so later. That has been the case for most of the pieces I have made, and it is how I have organized those movements in that particular space, in that particular time, with the framework given by the music. It is what I have taught myself to do over the last 30 years and, as I was reminded the other day, in the over 3500 times that my dance company Rosas has performed.

We have had the chance to bring some of those pieces to museum spaces. In 2011, MoMA invited us to do Violin Phase, part of my very first piece, Fase, from 1982, in the museum’s atrium. The piece had originally been conceived for the stage, but I had reimagined it for the film I made together with Thierry De Mey, which was set in a forest; filming, of course, allowed for different perspectives, for a different relation to the space and time of the work. At MoMA, the audience surrounded the work and saw it from above, so quite a different relation to the audience. We played even more with these possibilities when Tate Modern invited us to do Fase. There, we divided it over the day at fixed moments: at 11 o’clock, at 1 o’clock, performed like regular events. Actually, the time organization within the twenty minutes of the performance was not different from in the stage version of the performance, but the frontality was broken and people were sitting much closer. It was curious to observe the way people used to looking at sculpture or architecture reacted to this experience – to sitting around in a circle and watching the movements unfold, as opposed walking around and taking in a sculpture. It was the same piece every time, even if the experience of it changed in relation to the setting. But the Wiels’ s invitation, which is to make an exhibition as a performance, and a performance as an exhibition – and not simply to use the exhibition space as a set – is something quite different.

- Where is that difference for you, exactly? I ask because I know that in thinking about this project, it had seemed important not to have an exhibition about your work (in other words, with films, photographs, scripts, or other traces of pieces performed), but instead an exhibition of your work. And also not a presentation of choreography that happens to be in a white cube museal space in the place of the black box of the theater, but a choreography specifically imagined in relation to the practices and protocols of an exhibition: no stage, no frontality, the possibility of proximity…

A liquid space …

- Exactly. But also using the duration and daily ‹time› of an exhibition…

The invitation to do this project came as I was working on Vortex Temporum, choreographed to the music of the same name by late French composer Gérard Grisey, and it was a layered process, with elements accumulating gradually. The same is true for how I thought about the ‹time› of the piece when thinking about using it as the foundation for Work/Travail/Arbeid as an exhibition. I did not want to take the habits of theater into an art space; one response to that would have been to do a 15-minute piece, something tailored to the attention span of a gallery. What appealed to me, however, was exactly the opposite: the exhibition offered the possibility of expanding the activity of the movement over a long period. Usually, a dance performance brings the layers accumulated in the rehearsals together. Here, I thought it would be nice to see the simplicity, the beauty, of the physical movements as separate layers, to suggest the infinite combinations available to these layers. Vortex is built with seven voices; when I took them apart, I realized that the voices were just as beautiful apart, and this allowed for different combinations of sound and movement. As it happens, this is precisely what Grisey’s piece does. Starting with a very basic motif, Grisey goes on to expand and condense time, and this idea of expanding and condensing time or harmonic space is what I wanted to work with.

- Music has such an important role in your work; it has, from the very beginning, determined or even structured your choreographic writing—more even than other choreographers. And what you are saying here is that the particular relationship to music in Vortex, a piece that happens to be about time, not only framed your thinking about the piece for the stage, but is also framing the way you are reinventing it for the exhibition. As you suggest, the jump from theater to exhibition is not just a jump to another space but to another temporal protocol. So it is fitting that you should use precisely this piece to think through these questions…

Looking back at my earliest pieces, as I did recently while preparing books about them, I had the feeling that I had made a lot of works where spatial organization and the mathematical or geometrical patterns that are kind of underlying maps to my work had preoccupied me so much that I didn’t have time for time. So time was something that I really wanted to work on. On the other hand, I must say, when thinking about those early works like Fase, based on the minimal music of Steve Reich, Rosas danst Rosas, and Elena’s Aria, I was sort of surprised by their duration, by how slowly things progressed in the piece. I thought maybe that was in contradiction with the age I was at that point since when I made those pieces I was about 20 years old. It is not sort of the thing that you naturally connect with at an age, when often one typically wants things to go quickly; and yet in those early works there was this incredibly slow expansion in time.

Later, through the working with Ann Veronica Janssens and Michel François, two artists I have repeatedly collaborated with, we created different frameworks that invite you to look closely at things without getting impatient. It was really coming back to the same concern in a different way. So in that way, I think, in Vortex Temporum, and now, with Work/Travail/Arbeid, I am bringing together parameters, questions, and possible answers to thirty years of taking seriously dance and choreography as a way organizing movement in time and space. It has been a way to pursue further the thing that has always fascinated me most, and that is working with this basic tool, the body. It has been a long journey, observing the human body, especially in its skeletal and mechanical aspects but also as a social, emotional and intellectual body. And one of the beautiful things about the rehearsals we have done at Wiels is the closeness, the intimacy with this body, which is observed very differently when right next to you. While working on Vortex, instead of sitting in front to observe its development, I found myself sitting on the sides, and often at the back. A vortex is a spiraling movement – as you know, I have worked a lot with circular movements – and it is in the nature of the spiral to undermine any priority between front and back. So I knew there was potential here for the exhibition.

- Throughout working in this project with you, I have come to realize that Work/Travail/Arbeid in a way condenses so many of the elements – the geometries, the rigorous written structure, the relationship to music, this thinking about the body and about time and space – that have animated your work from the start. But more than that, you are also allowing the audience at Wiels to see this piece, not as it would be performed onstage, but as you worked or work on it: the different perspectives and layering of the work process, etc. And that, of course, gives us a clue to the title of the show: Work/Travail/Arbeid. The audience itself turns around, like the choreographer working with her dancers. Perhaps it would be interesting to say something about how a ‹theatrical›

piece becomes a ‹museum› piece?

The framework of Vortex Temporum is our starting point, and from there we deconstruct, we separate all the different layers. The voices separate, so that instead of working on seven voices together, we work on oneness, then on two-ness, on combinations of visual and auditive counter point. And then three-ness… and so on. I worked on cycles of nine hours that shift over the seven opening hours of the museum. What we are showing is the process, what we do to make a piece, step by step. We show all the single steps, not didactically, but experientially.

- One of the signatures of your choreographic practice is your minimalist approach, you pare down rather than build up. So here it is fitting that you have done the same: you chose not to intervene at the level of the architecture or add anything and you have chosen to use natural light as part of the ‹scenography›. This is relevant given that the audience can potentially come and stay as long as they like and the piece is constantly being built and unbuilt, evolving.

Yes, and it is circular, like a vortex. This raises questions about beginnings and endings: the work is continuous. And one of the challenges at Wiels has been how to get this continuous movement across a nine-week time span. I am also curious to see how the natural light will impact the work: we start in mid-March and end in May, so there will be a big change in the light. The decision to use the natural light as a subtle and changing but somehow important feature came out of my discussions with Ann Veronica Janssens, who I was very happy to be able to work with again and to involve in this particular project. As for the scenography, the only additions I have made are chalkdrawn geometrical patterns, the underlining frameworks of the piece, which will also expand and contract. When you go to the theater, you can sort of predict the collective experience that awaits you. But here it will be unpredictable: maybe it will be packed, or there will only be a couple of people there, and that will change your experience of the work.

- Indeed, more even than the numbers of visitors, you have no idea what the public will do here. In a way, of course, you never do, but in a theater there are seats, keeping people at a distance from each other and the stage. One thing about reconceiving dance as an exhibition is that the audience does know have a known protocol for their behavior: Will they sit or stand or talk or dance? Will they treat the work like sculpture in the round? Will they move through it?

The very experience of doing this exhibition will be a research into that aspect as well. The challenge is on the side of the audience, how they will interact with this work, and, for the dancers, how they will perform in such a context. We’re still discussing the implications of some of the possible outcomes and reactions, trying to anticipate but also knowing that there will be a great element of the unknown. But that is what work for me has always meant: a constant search, not only in the rehearsal process, but also in the performances themselves – and that will be no different here.

Elena Filipovic has been director of Kunsthalle Basel since 2014.

Previously, she was Chief Curator at Wiels in Brussels where she curated Work/Travail/Arbeid in 2015.

This interview was first published in the catalogue accompanying Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s exhibition Work/Travail/Arbeid at Wiels in 2015 (Brussels: Wiels, Rosas, Mercatorfonds, 2015). Reprint with kind permission by Rosas.